The William Webb Wagg investigation (3)

Part 3: William Wagg the Convict

What the Tasmanian records tell us

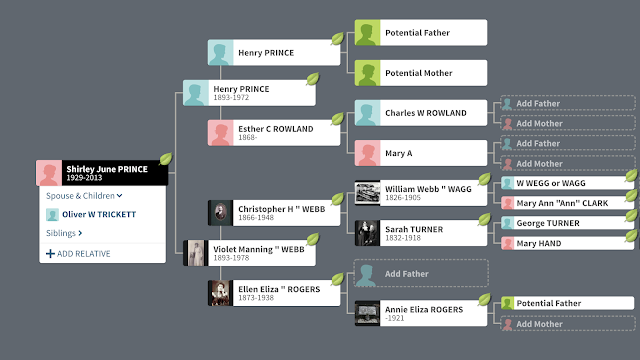

In Parts 1 and 2 of this series, I established that William Webb Wagg was not the child who arrived in New South Wales in 1837, and explored how the name Webb entered the family.

This post steps back further in time and brings together all of the convict records currently known for William, to understand who he was before he appeared in Sydney — and why the Tasmanian record of his life comes to an abrupt end.

Trial and sentence in England

|

England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 |

William Wagg was tried at the Norfolk Assizes in July 1843 and sentenced to seven years’ transportation. The criminal register for that year records him as 18 years of age and describes the offence as burglary, placing him among those convicted of serious property crime rather than minor theft. Burglary at this period typically involved unlawful entry into a dwelling or building with intent to steal and was treated as a felony offence. [1]

This detail is consistent across multiple records and firmly places William’s origins in Norwich, Norfolk, aligning with later Australian records and with the death notice that requested that “home papers” be asked to copy his death.

This English conviction marks the point at which William’s life enters the documentary record as a transported convict, a trail that continues in the Tasmanian records following his arrival in Van Diemen’s Land in June 1845.

Arrival in Van Diemen’s Land

William arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on 18 June 1845 aboard the Mount Stewart Elphinstone, having departed from London on 7 March 1845. At the time of arrival, he was recorded as 20 years of age, working as a labourer, with his native place given as Norwich, England. These details place his birth between 1824 and 1826, a range that remains consistent across his later Tasmanian records. [2]

Left: New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia, Convict Musters, 1806–1849, showing William Wagg listed in the 1846 Ledger Returns following his arrival aboard the Mount Stewart Elphinstone.

The Tasmanian Convict Record for William Wagg

The convict indent, compiled after his arrival, also preserves important information about the circumstances of his offence and the family connections he identified in England. [4]

Conviction and sentence in England

William Wagg appears in the records under convict number 15812. The Tasmanian record confirms that he was tried at the Norfolk Assizes on 31 July 1843, convicted of burglary, and sentenced to seven years’ transportation. The formal wording states that he was “convicted before the Recorder at the Assizes at Norfolk” and that the court pronounced sentence that he be “transported beyond the seas for the term of seven years.” At the time of conviction, his character is explicitly recorded as “good.”

Prior convictions and the circumstances of the offence

In addition to recording the Assizes conviction, the Tasmanian convict record provides a more granular account of the offence and William’s prior contact with the criminal justice system. It summarises the burglary as housebreaking at King Street, Norwich, involving the taking of an iron pot, and notes William’s own statement that he was "caught in the house". Despite the modest value of the item, housebreaking was regarded as a serious felony under English law, accounting for the transportation sentence that followed.

The record also shows earlier summary convictions for vagrancy, with custodial sentences of fourteen days and twenty-one days. These entries reflect minor offences dealt with summarily, involving short periods of confinement and are recorded as background context rather than as part of the transportation sentence itself.

Such detail reflects common practice of the period. Summary vagrancy convictions were frequently recorded alongside indictable offences to provide authorities with an assessment of social circumstances, previous conduct, and whether offending appeared isolated or escalating. In William’s case, the record suggests a progression from minor summary offences to a serious property crime, rather than a long pattern of repeated serious offending. The assessment of his character as “good” at the time of sentencing aligns closely with later Tasmanian remarks describing his conduct as “tolerably good since arrival.”

Family information recorded in the indent

Significantly, the Tasmanian convict indent also records family details provided by William himself. He identified his mother as Ann, a brother Christopher, and sisters Mary, Susan, and Adelaide. Such information was routinely gathered by Tasmanian authorities from transported convicts and represents William’s own account of his immediate family in England. These names take on added significance when viewed alongside the naming of William’s own children, which includes Mary Ann, Adelaide and Christopher, reflecting a continuity of family names across generations. While this pattern does not constitute proof in itself and requires independent corroboration, it provides rare and valuable clues to his origins and establishes a clear framework for further research in Norwich parish and civil records.

A physical portrait of William

|

William’s convict description provides a rare and unusually detailed physical portrait. He was recorded as five feet five and a quarter inches tall, with a fresh complexion, brown hair, grey eyes, and an oval face with a broad chin. Several identifying marks were also carefully noted including "W" on his left wrist, dots between the forefinger and thumb of his left hand, blue dots on the fingers of his right hand, and a scar on his left thumb.

Such descriptions were recorded with precision to ensure accurate identification within the convict system and to confirm that references across multiple records relate to the same individual. The indent also records that William was Protestant and unable to read or write, details that place him squarely within the social and educational realities of many working-class men of his generation.

Above: Illustrative reconstruction of William Webb Wagg at Port Cygnet, based on Tasmanian convict records and later family photographs.

Classification under the Probation System

On arrival in Van Diemen’s Land, William entered the Van Diemen’s Land probation system, under which convicts began as Third Class and progressed through the classes according to conduct and compliance. By 1846, William is recorded as Second Class, indicating that he had moved beyond the harshest early stage of probation and was regarded as generally compliant, working under government control, most likely in a probation gang.

This classification is significant. It shows that William was not immediately absconding, nor was he repeatedly offending in the early years of his sentence, but was instead progressing through the system in the expected manner.

Assignment to Port Cygnet

Probation Station at Lymington, Port Cygnet, Van Diemen’s Land (pencil and wash, Jan 11, 1848), showing the layout of the probation station and buildings, drawn by Simpkinson de Wesselow. [6]

Conduct and discipline

William’s conduct record during his time under probation is relatively brief. On 26 August 1845, shortly after his arrival in Van Diemen’s Land, he was reported for being drunk and disorderly and punished with solitary confinement. There is no evidence of repeated misconduct, and this incident appears to represent an early disciplinary lapse rather than an ongoing pattern of behaviour.

An administrative notation dated October 1846 records a change in William’s probation disposition. This entry does not correspond to a new offence, but instead reflects an internal adjustment to his status within the probation system — consistent with routine reviews of conduct, classification, or assignment. Taken together, these records suggest that William generally complied with the requirements of the system after his initial lapse and continued to progress through the established probation framework.

Revocation and disappearance

The most consequential entry in William’s Tasmanian record occurs on 24 July 1850, when his status is noted as “probation revoked — absent from muster.” This brief administrative notation carries significant weight.

By this point, William had advanced well beyond the early stages of the probation system. After his Second Class placement at Port Cygnet in 1846, subsequent muster records show that by 1849 he was holding a Ticket of Leave. [7] This status was granted only to men whose conduct was considered satisfactory and who were trusted to live and work independently, subject to reporting requirements and ongoing supervision.

Holding a Ticket of Leave did not remove all obligations. Men were still required to attend musters and comply with the conditions attached to that privilege. William’s failure to appear at muster in July 1850 therefore resulted in the formal revocation of his probationary status.

From that point onward, William effectively disappears from Tasmanian records. There is no subsequent assignment, no recorded punishment following revocation, and no formal notation of sentence completion or release. The record does not trail off through silence; instead, it explicitly marks the moment at which official oversight ended because William could no longer be located.

Such disappearances were not uncommon. Men whose probation or Ticket of Leave was revoked often left their assigned districts, crossed to the mainland, or took work at sea, slipping beyond the practical reach of colonial administration. What matters here is that the documentary record captures this transition precisely. This is not an absence of evidence, but evidence of absence — a documented break that explains why William ceases to appear in Tasmanian sources after mid-1850 and why his next appearance is found elsewhere.

Port Cygnet in context

Not all convict stations in Van Diemen’s Land were places of extreme punishment like Port Arthur; many, including Port Cygnet, functioned as working probation stations designed to control labour and gradually process convicts through the system.

At Port Cygnet, William was placed within one of the probation stations that formed the backbone of the Van Diemen’s Land system. Convicts were organised into government labour gangs and set to the heavy, unskilled work required to establish and maintain the station and its surrounding infrastructure. This was physically demanding labour carried out under close supervision and a strict daily routine.

The work was practical and relentless. Men cleared dense bush, felled timber, and prepared land for cultivation. They constructed huts, store buildings, and other basic structures necessary for the station’s operation, maintained tracks through rough terrain, and worked on jetties and shoreline facilities that connected the settlement to the wider coastal network. Agricultural labour—planting, tending, and harvesting crops to sustain the station—formed another part of daily life. As a Second Class probationer recorded simply as a labourer, William would have been assigned to this kind of general work rather than to any skilled trade or private employment.

Life at Port Cygnet followed a regulated rhythm: early rising, long hours of physical labour, meals taken at fixed times, and confinement to barracks under supervision. Discipline was present and enforced, but the station’s purpose was not primarily punitive. Instead, the emphasis was on work, routine, and gradual progression through the probation system for those who complied.

This experience differed markedly from that of convicts sent to Port Arthur, which many readers will recognise as the most infamous penal settlement in Van Diemen’s Land. Port Arthur functioned as a secondary punishment station, reserved for men who had already offended in the colony or seriously breached discipline elsewhere. Life there was deliberately harsh and isolating, shaped by strict surveillance, prolonged confinement, and punishments intended to deter further resistance. Where Port Arthur was designed to break men who had failed the system, Port Cygnet was designed to process men through it.

That distinction matters when considering William’s later disappearance from the records. Absconding from probation or failing to appear at muster carried real risks. Had William been apprehended, he could have faced severe consequences, including reassignment to a punitive station such as Port Arthur. The fact that he disappears from Tasmanian records after his probation was revoked suggests not recklessness, but an awareness of what capture might entail.

William’s placement at Port Cygnet therefore situates him firmly within a working probation environment, not a punitive one. It reflects a period of enforced labour and routine consistent with his generally acceptable conduct during these years and with his later progression within the system. It also helps explain what followed. Time spent in a coastal settlement—clearing land, maintaining jetties, and living alongside maritime activity—made familiarity with the sea an ordinary part of daily life. In that context, later maritime employment was not an abrupt change of direction, but a plausible continuation once William slipped beyond the reach of the probation system.

What the convict records establish — and what they do not

Taken together, the convict records establish that William Wagg:

was born in Norwich, England

was convicted of burglary at the Norfolk Assizes in 1843 and sentenced to seven years’ transportation

arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1845 aboard the Mount Stewart Elphinstone

entered the probation system as Third Class, progressed to Second Class, and was stationed at Port Cygnet by 1846

had generally acceptable conduct, with one early disciplinary lapse

qualified for and held a Ticket of Leave by 1849

had his probation formally revoked in July 1850 after failing to appear at muster

disappears from Tasmanian records after that date, with no further assignment, punishment, or record of release

The records do not tell us precisely how William left Tasmania, how he supported himself immediately after absconding, or under what circumstances he transitioned into maritime work. What they do document, however, is the exact point at which official oversight ended, creating a clearly defined break in the Tasmanian record.

By 1853, this same man — our ancestor William Webb Wagg — next appears in Sydney, working at sea under the name William Webb and marrying Sarah Turner under the name William Wagg. While the documentary record does not yet establish precisely how or when he moved from the Tasmanian probation system into maritime employment, the continuity of age, place of origin, timing, naming patterns, and later family records leaves little doubt that these records describe the same individual. What remains unresolved is not his identity, but the mechanism by which that transition occurred.

Why this matters

Understanding William’s convict past is not about labelling or judgement. It is about continuity.

The Tasmanian records explain why William does not appear in New South Wales before the early 1850s, why his movements during those years are difficult to trace, and why maritime work emerges as a plausible and coherent next step rather than an abrupt change of direction. They provide the missing middle chapter between his origins in Norwich and his settled life at North Sydney.

Seen in this light, William’s later re-emergence is not a mystery detached from the past, but a continuation shaped by the structures, opportunities, and risks of the probation system itself.

Looking ahead

In the next part of this investigation, attention turns back to England: to what can — and cannot — be established about William’s early life and family in Norwich. It is at this point that DNA evidence becomes particularly important, not as a substitute for the documentary record, but as a means of testing, refining, and strengthening it where traditional sources fall silent.

*****************************

William Webb Wagg investigation series

This post forms part of the ongoing investigation into the origins of William Webb Wagg. The full series, including all published posts and supporting material, can be accessed here:

View the complete investigation series:

https://webbwagg.blogspot.com/p/the-william-webb-wagg-investigation.htmlSeries navigation:

→ Next post: Roots in Norwich, Norfolk

******************************

[1] England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791–1892, record for William Wagg, tried at the Norfolk Assizes on 31 July 1843 and sentenced to transportation; age recorded as 18, with an estimated birth year of about 1825.

[2] New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia, Convict Musters, 1806–1849, Ledger Returns S–Z (1846), entry for William Wagg; arrived 1845 aboard Mount Stewart Elphinstone; place of conviction: Norfolk.

[3] Libraries Tasmania, Tasmanian Convict Indents, CON33-1-66, p. 257, entry for William Wagg; records offence details (housebreaking, King Street, Norwich), prior vagrancy convictions, physical description, identifying marks, and family information provided in the indent.

[4] Excerpt from Tasmanian Convict Indent, CON14-1-21, p. 267, 268 (Libraries Tasmania), recording William Wagg’s offence and family details.

[5] New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia, Convict Musters, 1806–1849, Ledger Returns S–Z, 1846; entry for William Wagg, arrived 1845 aboard Mount Stewart Elphinstone, convicted in Norfolk; Tasmania. Digital image.

[6] “Probation Station at Lymington, Port Cygnet, Van Diemen’s Land,” pencil and wash illustration, January 11, 1848, drawn by Simpkinson de Wesselow; object no. 1961220, eHive collection, University of Tasmania Special and Rare Materials Collection.

[7] New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia, Convict Musters, 1806–1849, Ledger Returns (1849); entry for Wm Wagg, arrived aboard Mount Stuart Elphinstone, place of conviction: Norwich; Tasmania. Digital image.