The William Webb Wagg investigation (5)

Part 5: Testing the Wegg family structure with DNA evidence

Scope and purpose

This post examines whether autosomal DNA evidence supports the documentary reconstruction of the Norwich Wegg family developed in earlier stages of this investigation.

That reconstruction was built using parish registers, census records, naming patterns, chronology, and migration context, and accommodates William Webb Wagg’s separation from his family through transportation to Australia, proposing a coherent family structure within which he plausibly fits.The purpose of the present analysis is not to generate new hypotheses, but to test whether the genetic relationships predicted by that documentary framework can be observed among known descendants when examined at scale.

The DNA analysis presented here follows established best practice in genetic genealogy. Rather than relying on individual centimorgan values — which are highly variable at this generational distance — it focuses on shared-match patterns observed across multiple independent descendant lines. At this generational distance, even genealogically legitimate relatives may share little or no detectable autosomal DNA due to the random nature of recombination. Consequently, low or absent shared-DNA values do not constitute evidence against a relationship on their own.

The scope of this post is deliberately limited. It does not attempt to resolve every outstanding question within the broader Webb Wagg family, nor does it claim a level of precision beyond what autosomal DNA can reasonably provide. Its purpose is narrower and more specific: to determine whether the reconstructed Norwich Wegg family is genetically coherent, and whether the available DNA evidence is consistent with the placement of William Webb Wagg within that structure.

At its heart, this analysis asks a simple question: Do the patterns of shared DNA between known descendants make sense if William Webb Wagg really belonged to the Norwich Wegg family we have reconstructed from records? DNA doesn’t prove documentary hypotheses by itself — but when it aligns consistently with records, it strengthens confidence in the overall reconstruction.

This analysis is written primarily for readers familiar with documentary genealogy and autosomal DNA interpretation, including experienced family historians and genetic genealogy researchers. Technical detail is included where necessary to make the reasoning transparent and reproducible. At the same time, the underlying question is a straightforward one: whether the family structure reconstructed from historical records is also supported by DNA evidence.

Introduction

In the preceding post, the Wegg family of Norwich was reconstructed using documentary evidence drawn from parish registers, civil registrations, and census records. That reconstruction identifies William and Mary Ann (Clark) Wegg as the parents of a group of children born in Norwich between 1819 and 1836, and places William Webb Wagg as the fourth of eight children and the third of seven who survived childhood.

William Webb Wagg was the only known member of this family to leave England, having been transported to Van Diemen’s Land as a convict. No evidence has been identified to suggest that any of his siblings emigrated, and all are otherwise documented as having remained in England.

The purpose of this post is to assess whether the DNA evidence from William Webb Wagg’s descendants aligns with the Norwich family structure established through documentary sources. The DNA evidence is examined here as an independent and complementary line of evidence, testing — rather than replacing — the conclusions drawn from the historical record.

Reader heads-up: Some of the terminology and concepts below (centimorgans, shared-match clusters) may be new to some readers. If you’re familiar with genetic genealogy, you’ll recognise these terms. If not, rest assured we’re using them in service of answering the question above — and you can always return to this section if you need a refresher as you read on.

A note on terminology

Because this analysis relies on autosomal DNA evidence, a brief clarification of terms may be helpful for some readers.

At the generational distance examined here, individual shared-DNA amounts (measured in centimorgans, or cM) can vary widely, and their absence or presence in any single comparison is not, by itself, decisive. What becomes more informative is the pattern in which matches occur.

A shared match is a DNA match who appears in the match lists of two or more testers, indicating a likely connection through a shared ancestral line. When multiple shared matches also match one another, they form a shared-match cluster. Such clusters are particularly valuable because they reduce the likelihood of coincidental or misleading matches and instead reflect inherited relationships from a common ancestor.

In this post, emphasis is therefore placed on shared-match clusters observed across multiple independent descendant lines, rather than on isolated matches or centimorgan values considered in isolation.

• Cluster: a group of shared matches that all interconnect — much stronger evidence of common ancestry.

I. Scope and purpose of the DNA analysis

The purpose of this DNA analysis is not to construct a family structure in the absence of records, but to test the documentary reconstruction of the Wegg family of Norwich established in the preceding post. That reconstruction identifies William Webb Wagg as one of the children of William and Mary Ann Wegg, born into a Norwich family whose members otherwise remained in England.

As shown previously, William Webb Wagg was the only member of this immediate family to leave England, having been transported first to Van Diemen’s Land and later appearing in New South Wales. No documentary evidence has been identified to suggest that any of his siblings migrated to Australia. As a result, any biological connection between William Webb Wagg and the Norwich family must be assessed indirectly, through the DNA of his descendants and their relationship to descendants of his proposed English siblings.

This post therefore examines autosomal DNA evidence from descendants of William Webb Wagg and compares it with DNA evidence from descendants of his proposed siblings, in order to assess whether the observed genetic relationships are consistent with the family structure reconstructed from documentary sources.

II. Overview of the DNA evidence used

The DNA evidence used in this analysis consists of autosomal DNA (atDNA) test results from the AncestryDNA database. Autosomal DNA is inherited from all ancestral lines and, when assessed across multiple independent descendant lines, is now well suited to investigating relationships within the last four to eight generations — the relevant timeframe for the Wegg family.

The analysis draws on results from multiple descendants of William Webb Wagg and from multiple, independent descendant lines of his proposed siblings in England. The use of several descendant lines is critical. No single DNA match is treated as determinative; instead, the analysis focuses on patterns observed across groups of matches, reducing the likelihood that conclusions rest on chance inheritance, endogamy, or undocumented relationships.

No Y-DNA or mitochondrial DNA evidence is used at this stage of the investigation. The focus is exclusively on autosomal evidence, assessed in conjunction with the previously established documentary framework.

Before examining specific match patterns, it is important to understand the methodological principles that guide how autosomal DNA evidence is interpreted in this context. The following section outlines the reasoning framework used throughout the analysis.

III. Methodological approach to the DNA evidence

Autosomal DNA results at AncestryDNA are expressed in centimorgans (cM), a unit that reflects the amount of shared genetic material between two individuals. In general terms, higher shared centimorgan values indicate closer biological relationships, while lower values reflect more distant ones. However, centimorgan values alone are insufficient to establish precise relationships, as inheritance is variable and overlapping ranges exist between different relationship types.

For this reason, the analysis does not rely solely on total shared DNA. Instead, it combines three complementary features of autosomal DNA evidence:

Shared centimorgan ranges, assessed in the context of plausible relationships given the documentary reconstruction

Shared-match patterns, which identify groups of testers who share DNA with each other as well as with the test subject

Consistency across multiple independent descendant lines, rather than isolated pairwise matches

Shared matches are particularly important in this analysis. When two individuals both match the same third party — and that third party can be placed within a known family line — the shared match contributes evidence toward a common ancestral source. When that same pattern is observed repeatedly across testers descended from different children of the same ancestral couple, the cumulative weight of the evidence increases substantially.

In practical terms, the analysis looks for clusters of shared matches linking descendants of William Webb Wagg to descendants of his proposed siblings, rather than to unrelated or alternative family groups. The absence of competing shared-match clusters pointing to a different parental family is treated as significant, though not conclusive on its own.

Throughout this post, the DNA evidence is interpreted in dialogue with the documentary record, not in isolation. The question being asked is not “What family does the DNA suggest?”, but rather:

Does the DNA align with the family already reconstructed from historical records?

IV. Expected DNA patterns if the reconstruction is correct

If the documentary reconstruction of the Wegg family of Norwich is correct, certain DNA patterns should be observable among the descendants of William Webb Wagg and the descendants of his proposed siblings.

As William Webb Wagg is positioned as one of a group of siblings born to the same parental couple, and given the generational distance between that sibling group and present-day testers, the closest expected genetic relationships between their descendants fall at the third-cousin level. In practice, however, most observed relationships are expected to be fourth cousins or more distant. Relationships closer than third cousins — such as half-siblings, first cousins, or avuncular connections — would not be consistent with the documented chronology of the family.

At these degrees of relatedness, autosomal DNA sharing is typically modest and highly variable. Third- and fourth-cousin relationships often share only small amounts of DNA, frequently measured in a few tens of centimorgans or less. Some legitimate relationships at this distance share little or no detectable DNA, while others share more than average. For this reason, individual centimorgan values are not interpreted in isolation, and no single match is treated as determinative.

Instead, if the reconstruction is correct, descendants of William Webb Wagg should share DNA with multiple, independent descendant lines of his siblings where such lines are represented in the DNA dataset. These shared matches should recur across different testers and across different sibling lines, forming overlapping clusters of shared matches rather than isolated pairwise connections.

Equally important is what should not be observed. If the reconstruction is correct, shared matches linking William Webb Wagg’s descendants should not consistently point toward an alternative parental family or coalesce around a different ancestral couple. While the absence of a particular expected match cannot, by itself, disprove a relationship — especially at fourth-cousin distance and beyond — the repeated convergence of shared matches on the same Norwich family across independent lines would be expected.

Given the structure of the Norwich sibling group and the generational distance involved, the most likely relationships between present-day descendants of William Webb Wagg and descendants of his siblings fall within the range of third cousins once removed (3C1R), third cousins twice removed (3C2R), fourth cousins (4C), and fourth cousins once removed (4C1R).

Reference to the Shared cM Project, as summarised by DNA Painter, provides a useful contextual guide to the expected scale of shared DNA at these relationship levels. Mean shared centimorgan values for these relationships are modest and highly variable — approximately 48 cM (3C1R), 36 cM (3C2R), 35 cM (4C), and 28 cM (4C1R) — with substantial standard deviations. As a result, considerable overlap between these categories is expected, reinforcing the need to interpret centimorgan values as contextual indicators rather than precise measures.

Interpretation of expected DNA patterns must also take into account AncestryDNA’s reporting thresholds, which affect what can be observed in practice. At present, AncestryDNA reports shared matches only above 20 cM by default, while matches between 7 cM and 20 cM are visible only when examining an individual tester’s full match list. The AncestryDNA ProTools Enhanced Shared Matching tool does not alter these thresholds, but makes it easier to identify and analyse shared matches below 20 cM where access to a tester’s full match list is available. Matches below 7 cM are not reported.

As many relationships at the fourth-cousin level and beyond are expected to share less than 20 cM of autosomal DNA, the absence of an observable shared match does not imply the absence of a biological relationship. Instead, it may reflect the limits of platform-level visibility, particularly where access to a tester’s full match list is not available.

Key takeaway before we look at results: DNA evidence at deeper cousin-level distances is inherently variable. That means we don’t look at single matches in isolation. Instead, we look for patterns across multiple independent lines — because recurring patterns are much less likely to be due to coincidence. Later sections will show these kinds of patterns.In summary, the anticipated DNA pattern is one of convergence rather than singularity: predominantly fourth-cousin–level (or more distant) relationships, occasional third-cousin–level connections, consistent shared-match clustering across multiple descendant lines, and no competing pattern pointing to a different family structure.

With these expectations established, the sections that follow examine the observed shared-match patterns among descendants of William Webb Wagg and the descendants of his proposed siblings. The emphasis is on whether the overall pattern — rather than any single centimorgan value — aligns with the family structure reconstructed from documentary evidence.

In practical terms, these expectations mean that the genetic evidence we observe should resemble a network of repeated connections across different descendant lines rather than isolated similarities between pairs — a pattern that would support the documentary reconstruction if present.

V. Description of the tested descendant groups

The DNA evidence draws on autosomal DNA test results from thirty two descendants of William Webb Wagg, together with results from descendants of two of his proposed siblings identified in the Norwich reconstruction, all tested through AncestryDNA.

On William Webb Wegg’s side, the dataset includes DNA results from descendants of all six children who survived to adulthood, representing multiple branches of his Australian family. These lines are genealogically independent of one another beyond their shared descent from William and Sarah (Turner) Webb Wagg within the documented timeframe of this analysis. While more distant common ancestry cannot be excluded, no such alternative ancestral signal is apparent in the observed shared-match patterns, which consistently align with the Webb Wagg and Turner lines.

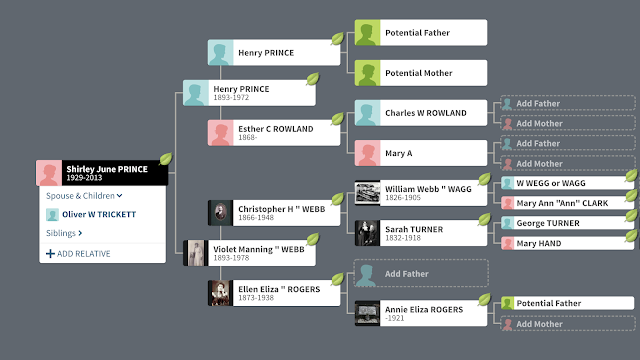

This coverage is illustrated in Figure 1, which maps the thirty two descendants of William Webb Wagg through each of his six surviving children and highlights those individuals whose AncestryDNA results are included in this analysis. The inclusion of descendants through Charles Webb Wagg reflects earlier work establishing his paternity of Beatrice Worrie using autosomal DNA evidence, which is documented separately and not re-examined here. [1]

|

| Figure 1 - Descendants of William Webb Wagg who have tested at AncestryDNA |

Individuals highlighted in orange are testers for whom I have access to the full AncestryDNA match list, enabling detailed shared-match analysis. Individuals highlighted in yellow are known testers for whom full match-list access is not available.

For these latter testers, analysis is constrained by AncestryDNA’s 20 cM reporting threshold for shared matches. At the generational distance relevant to this study — where most relationships fall at fourth-cousin level or beyond — this threshold limits the range of observable matches. All matches sharing 20 cM or more were informative and have been incorporated into the analysis. Accordingly, detailed shared-match clustering relies primarily on the nine testers for whom full match-list access is available, with higher-level matches from other testers contributing additional supporting evidence where observed.

Table 1 summarises the tested descendants shown in Figure 1, indicating the child of William Webb Wagg through whom each tester descends and their relationship to him.

Table 1 Tested descendants of William Webb Wagg by child line

| Child of William Webb Wagg | Descendant line(s) represented | Relationship of testers to William Webb Wagg |

|---|---|---|

Sarah Jane | Descendants via Elvin Gillett line | 3x Great-grandchild |

Charles | Descendants via Beatrice Worrie line | 2X, 3X and 4X Great-grandchildren |

| Christopher | Descendants via the Violet and Mabel Webb lines | 2X Great-grandchildren and 4X Great-grandchild |

| Albert Hayden | Descendants via the Ethel, Henry, John, and Stanley Webb Wagg lines | Great-grandchildren and 2X Great-grandchildren |

| William | Descendants via the William and Charles Webb Wagg lines | 2x Great-grandchildren |

| Minnie | Descendants via the William and Arthur Neely lines | Great-grandchildren, 2X and 3X Great-grandchildren |

With DNA testers now represented across all six descendant branches of William Webb Wagg, it is possible to move beyond individual matches and examine whether the shared-match patterns observed across these independent lines align with the Norwich family structure reconstructed from documentary evidence.

VI. Observed shared-match patterns

When the autosomal DNA evidence is examined in light of the expectations outlined in Section IV, the observed shared-match patterns are coherent and internally consistent.

Across multiple descendants of William Webb Wagg, shared matches are observed with descendants of his proposed siblings within the Norwich Wegg family. These matches fall within the expected centimorgan ranges for predominantly fourth-cousin-level relationships, with occasional values consistent with third-cousin connections. As anticipated at this generational distance, individual centimorgan values vary and are not interpreted in isolation.

The analytical strength of the evidence lies not in any single match, but in the repetition of the same shared-match patterns across independent descendant lines. Different Australian branches of William Webb Wagg repeatedly share DNA with the same English sibling lines, and those English lines, in turn, share DNA with one another in ways consistent with descent from a common parental couple.

Rather than appearing as isolated or sporadic pairings, these shared matches form overlapping clusters that link descendants of William Webb Wagg to descendants of specific Norwich siblings and their children. Where more than one sibling line is represented, the observed patterns are mutually reinforcing rather than contradictory, and are observed across multiple descendant branches rather than being confined to a single line.

At this point, it is helpful to consider the structure of the Norwich sibling group and the extent to which DNA evidence is currently available across those lines.

|

| Figure 2 - Webb–Clark sibling group and descendant DNA representation |

This chart places William Webb Wagg within the broader sibling group of William and Mary Ann (Clark) Wegg and illustrates the extent to which autosomal DNA evidence is presently available across that family. Of the six children who survived to adulthood, autosomal DNA evidence is currently represented through descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg, whose lines remain extant and identifiable within the AncestryDNA database.

William Webb Wagg’s own descendants form the Australian test group in this analysis. Tested descendants from the English-based sibling lines are identified separately as shared matches. Comparison between these two groups — Australian descendants of William Webb Wagg and English descendants of his siblings — forms the basis of the sibling-level DNA analysis undertaken in this post.

The chart also distinguishes between differing levels of documentary certainty and DNA accessibility. Sibling lines shown in yellow — Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg — represent branches for which descendant lines have been identified and at least one descendant has undertaken autosomal DNA testing at AncestryDNA, but for whom I do not have access to full match lists. For these testers, analysis is limited to shared matches reported at or above AncestryDNA’s 20 cM threshold, except where those matches occur with one of the nine testers for whom full match-list access is available, allowing deeper shared-match analysis.

Sibling lines shown in orange — Mary Ann Wegg and Adelaide Wegg — represent branches where documentary evidence suggests possible living descendants, but no identifiable autosomal DNA matches attributable to those lines have yet been located within AncestryDNA. This may reflect a lack of testing, incomplete or private family trees, or the absence of detectable autosomal DNA at this distance. The absence of matches from these lines is therefore treated as neutral rather than as negative evidence.

The remaining two siblings — Elizabeth Wegg and Christopher Henry Wegg, shown in green — have no known living descendants. No autosomal DNA representation is expected from these lines, and their absence from the shared-match analysis is fully accounted for by documentary evidence.

Importantly, no competing shared-match cluster has been identified that consistently points toward an alternative parental family for William Webb Wagg. While the absence of a particular expected match is not treated as disproof — especially at fourth-cousin distance and beyond — the absence of a coherent alternative pattern is itself notable. The shared matches observed consistently align with the Wegg sibling lines already established through documentary research.

It is also worth emphasising what we do not observe. Some descendant lines show little or no detectable shared DNA with specific English lines — a pattern entirely consistent with expected inheritance variability at the fourth-cousin level and beyond. The absence of detectable DNA in some cases should not be taken as evidence against the reconstructed relationship; rather, it reflects the stochastic nature of autosomal inheritance.

Taken together, the observed shared-match behaviour accords with expectations for a sibling group separated by geographic distance, with one line established in Australia and the others remaining in England. The DNA evidence therefore behaves in a manner consistent with the reconstructed Norwich family structure.

The following sections examine this evidence sibling by sibling, focusing on the two represented lines — Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg — and assessing whether the DNA patterns associated with each continue to align with the documentary reconstruction.

Sarah Ann Wegg: documentary context

Sarah Ann Wegg, the second child of William and Mary Ann Wegg, was born in 1822 in Norwich, Norfolk. She married Charles Gerald Hagon, also Norwich-born, and the couple later relocated to London, where both spent the remainder of their lives. Charles Hagon died in 1877, and Sarah Ann died in 1884, aged 62.

Sarah Ann and Charles Hagon had six known children, born between the early 1840s and late 1850s. Documentary records indicate a mixed pattern of survival within the family. Two children — William Hagon and Susannah Hagon — died in childhood. A third child, Mary Ann Hagon, appears in early records but cannot be traced beyond young adulthood; no definitive marriage or death record has yet been identified for her after her appearance as a young woman in the 1871 census.

Three children — Charles Hagon, Elizabeth Hagon, and Adelaide Emma Hagon — reached adulthood and married. While documentary information for Elizabeth Hagon remains limited and no confirmed death record has yet been identified, autosomal DNA evidence has been identified through one of her children, confirming the continuation of this line beyond the surviving documentary record. Together with the documented descendant lines of Charles Hagon and Adelaide Emma Hagon, this establishes multiple independent avenues of descent from the Sarah Ann Wegg branch.

Susannah Wegg: documentary context

Susannah Wegg, the sixth child of William and Mary Ann Wegg, was born in 1830 in Norwich, Norfolk. In 1858 she married Frederick Hagon, also born in Norwich and the brother of Charles Gerald Hagon, who married Susannah’s sister Sarah Ann Wegg. The couple settled in London, where they spent the remainder of their lives. Frederick Hagon died in 1901, and Susannah died in 1911, aged 80.

Susannah and Frederick Hagon had four known children, all born in Lambeth, London. Documentary evidence shows that Henry Hagon died in infancy. Alice Hagon did not marry and has no known children. Arthur Hagon married Daisy Eliza Stevens, but no children have been identified from this union in available records.

The remaining child, Sarah Ann Hagon, is documented as having descendants. She married George Leeks in 1884 and, following his death, remarried Thomas Gale in 1903. It is through this Sarah Ann Hagon line that the Susannah Wegg branch continues into later generations.

Observed shared autosomal DNA between William Webb Wagg and his sisters' descendants

|

| Chart 3 - Descendants of William Webb Wagg who have tested at AncestryDNA |

The chart above summarises the observed shared autosomal DNA relationships between tested descendants of William Webb Wagg and tested descendants of his sisters Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg. It brings together, in a single visual, both the presence and absence of shared DNA and the practical limits imposed by match-list access at AncestryDNA.

Each coloured box represents a tested descendant of William Webb Wagg. Colour is used to indicate both whether shared DNA is observed with descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg and/or Susannah Wegg and the level of analytical access available:

Orange indicates that the William Webb Wagg descendant shares autosomal DNA with one or more tested descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg and/or Susannah Wegg and that I have access to the full AncestryDNA match list. These testers form the core analytical group, as their shared-match networks can be examined in detail.

Yellow indicates that shared autosomal DNA is present between the William Webb Wagg descendant and one or more tested descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg and/or Susannah Wegg, but that I do not have access to the match list. In these cases, shared DNA at or above AncestryDNA’s 20 cM reporting threshold is visible and has been incorporated into the analysis, but deeper shared-match clustering cannot be examined.

Green indicates that I have access to the match list for the William Webb Wagg descendant, but no shared autosomal DNA is observed with the tested descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg or Susannah Wegg. Given the expected fourth-cousin–level (or more distant) relationships involved, this absence is not unexpected and does not constitute negative evidence.

Blue indicates that I do not have access to the match list and that the William Webb Wagg descendant does not share 20 cM or more with any tested descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg or Susannah Wegg. At this generational distance, such non-sharing is well within expectations and cannot be interpreted in isolation.

The chart therefore makes two points immediately clear.

First, shared DNA links between William Webb Wagg’s descendants and the descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg are observed repeatedly across multiple, independent branches of William Webb Wagg’s Australian family. These links are not confined to a single descendant line but recur across different branches, consistent with expectations for sibling-level relationships separated by migration and multiple generations.

Second, the observed pattern is asymmetric but coherent, and that coherence is visible across successive generational layers of William Webb Wagg’s descendants. All four tested great-grandchildren of William Webb Wagg share autosomal DNA with one or more descendants of his sisters. Among the fifteen tested second great-grandchildren, eleven show shared DNA with descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg and/or Susannah Wegg. At greater generational distance, the signal predictably attenuates but does not disappear: three of eight tested third great-grandchildren and two of five tested fourth great-grandchildren also share detectable DNA with the same sibling lines.

This progressive decline in detectable sharing with each additional generation is entirely consistent with known autosomal inheritance behaviour at third- and fourth-cousin distance and beyond. Some descendant lines retain detectable shared DNA, while others do not, reflecting the stochastic nature of recombination rather than any structural inconsistency in the reconstructed family. Where shared DNA is observed, it continues to align with the same two sibling branches, reinforcing the coherence of the pattern rather than fragmenting it. Importantly, there is no competing pattern in which shared DNA consistently clusters around an alternative sibling line or an unrelated family group. Where shared DNA is observed, it aligns specifically with the Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg branches already identified through documentary research.

The sections that follow examine the shared DNA associated with the orange and yellow testers in more detail, focusing on centimorgan values, shared-match clustering, and the repeatability of these patterns across independent descendant lines.

The two matrices that follow (Tables 2 and 3) summarise the observed shared autosomal DNA between descendants of William Webb Wagg and descendants of Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg. Shared DNA is reported in centimorgans (cM). A dash (–) indicates that no shared DNA is observed or that any shared DNA falls below AncestryDNA’s reporting threshold. “n/a” indicates that match-list access is unavailable and shared DNA below 20 cM cannot be assessed.

|

| Table 2 - Click on image to enlarge |

|

| Table 3 - Click on image to enlarge |

Across both sibling lines, autosomal DNA matches recur across multiple, independent descendant branches of William Webb Wagg. In the case of Sarah Ann Wegg, DNA representation is observed through several independent child lines. For Susannah Wegg, representation derives from more than one tested descendant branch descending from Sarah Ann Hagon. This difference in coverage reflects the documented family structures of the two branches and does not affect the interpretation of the results.

Observed centimorgan values fall within the expected ranges for predominantly fourth-cousin–level relationships, with occasional values consistent with third-cousin–level connections. More importantly, the same descendant lines recur as shared matches across independent Australian descendant branches of William Webb Wagg, forming coherent and repeatable shared-match clusters rather than isolated pairwise connections.

Equally important is what is not observed. No competing shared-match cluster has been identified that consistently points toward an alternative parental family for William Webb Wagg. While the absence of a particular expected match is not treated as disproof — especially at fourth-cousin distance and beyond — the absence of a coherent alternative pattern is itself informative.

Taken together, the shared DNA behaviour associated with the Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg branches aligns closely with the documentary reconstruction of the Norwich Wegg family and provides positive genetic support for William Webb Wagg’s placement within this sibling group.

Mary Ann Wegg: documentary context

Mary Ann Wegg, the eldest child of William and Mary Ann Wegg, was born in 1819 in Norwich, Norfolk. She married Robert Allen in 1842, and the couple remained in Norfolk for the rest of their lives. Robert Allen died in 1885, and Mary Ann died in 1894, aged 74.

Mary Ann Wegg and Robert Allen had four children — Elizabeth, Robert, Hannah, and Frederick Charles Allen — all born in Norwich. Of these, Frederick Charles Allen was the only child known to have descendants. Frederick later emigrated to Australia in the late nineteenth century, settling in Melbourne, where he married Fanny Maria Lowe in 1890. He and his wife had seven children who survived to adulthood, several of whom married and had children of their own.

Frederick Charles Allen was therefore the only other known member of the immediate Wegg family network to settle in Australia. He was a nephew, rather than a sibling, of William Webb Wagg. His presence in Australia represents a limited parallel migration within the extended family and does not alter the expected degree of genetic relatedness between his descendants and those of William Webb Wagg.

Adelaide Wegg: documentary context

Adelaide Wegg, the youngest child of William and Mary Ann Wegg, was born in 1833 in Norwich, Norfolk. She married Robert Fletcher in Norwich in 1853, and the couple remained there for the remainder of their lives. Adelaide died in 1886, aged 52, and Robert Fletcher died later the same year.

Adelaide and Robert Fletcher had six children, all born in Norwich: Robert Christopher, Elizabeth Sarah, Adelaide, Mary Ann, Clara, and Samuel Fletcher. Documentary evidence indicates that three of these children — Robert Christopher Fletcher, Adelaide Fletcher, and Samuel Fletcher — died without issue. The remaining three — Elizabeth Sarah, Mary Ann, and Clara Fletcher — married and are known to have had children.

DNA representation of the Mary Ann and Adelaide Wegg lines

Despite the existence of documented descendant lines through both Mary Ann Wegg and Adelaide Wegg, no identifiable autosomal DNA matches attributable to either line have been observed to date within the AncestryDNA dataset examined in this analysis. This absence may reflect a lack of tested descendants, incomplete or inaccessible family trees, platform reporting thresholds, limitations in reconstructing descendant lines with confidence, or the expected loss of detectable autosomal DNA at fourth-cousin distance and beyond.

The absence of DNA representation from these two sibling lines is therefore treated as neutral and does not weigh against the reconstructed family structure. Importantly, no shared-match patterns associated with either line point toward an alternative parental family for William Webb Wagg, nor do they conflict with the DNA evidence observed from the represented sibling lines.

From analysis to findings

Taken together, the observed shared-match patterns align closely with the relationships predicted by the documentary reconstruction of the Norwich Wegg family. Matches recur across multiple independent descendant lines in configurations consistent with William Webb Wagg belonging to the same sibling group as the children of William and Mary Ann (Clark) Wegg, rather than appearing as isolated or anomalous connections.

Although autosomal DNA cannot identify a specific parent–child relationship at this generational distance, the consistency and distribution of shared matches provide independent support for William Webb Wagg’s placement within the reconstructed family structure. In particular, shared-match patterns across the Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg lines display a high degree of internal consistency, with shared autosomal DNA repeatedly observed across multiple Australian descendant branches and multiple English sibling lines.

Where shared DNA is not observed, its absence is fully consistent with documented family structures, known descendant availability, and the expected loss of detectable autosomal DNA at fourth-cousin distance and beyond. Centimorgan values fall within appropriate ranges, and no competing shared-match clusters point toward an alternative parental family. The observed variation reflects normal autosomal inheritance rather than structural inconsistency.

At this stage, the analysis moves beyond individual matches or sibling branches. What matters is the overall pattern that emerges when documentary and autosomal DNA evidence are considered together. The final section therefore steps back to assess the Wegg family structure as a whole, drawing together the cumulative evidence to evaluate whether it converges on a single, coherent conclusion.

Summary of evidence so far:

Before we close the analysis, it’s worth recapping:

Documentary evidence places William Webb Wagg as one of the Norwich Wegg siblings.

DNA shared-match cluster patterns align repeatedly with the same sibling lines.

- No alternative family cluster consistently explains the DNA patterns.

Taken together, this strengthens the case that the DNA behaviour we see is consistent with the reconstructed family — not contradictory to it.

VII. Synthesis: assessing the Wegg family structure as a whole

The purpose of this analysis has been to assess whether the family structure reconstructed for the Wegg family of Norwich using documentary evidence is consistent with the autosomal DNA evidence now available from multiple descendant lines. The question is not whether every expected relationship can be demonstrated, but whether the cumulative evidence converges on a single, coherent explanation.

Documentary evidence identifies William Webb Wagg as one of a group of siblings born to William and Mary Ann (Clark) Wegg in Norwich, with all siblings except William remaining in England. Any biological connection between William Webb Wagg and his siblings must be assessed indirectly, through autosomal DNA shared among their descendants several generations later.

The autosomal DNA evidence behaves in a manner consistent with that reconstruction. Shared autosomal DNA is repeatedly observed between descendants of William Webb Wagg and descendants of his sisters Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg—the two sibling lines for which both documentary continuity and tested descendants are clearly identifiable. These shared matches recur across multiple independent Australian descendant branches of William Webb Wagg, rather than being confined to a single line or individual tester.

As expected at third- and fourth-cousin distance and beyond, the pattern of sharing is uneven. Not every descendant shares detectable DNA, and shared centimorgan values vary across generations. This asymmetry reflects the stochastic nature of autosomal inheritance and the known limits of detectability at this depth, rather than inconsistency in the underlying family structure.

The generational distribution of observed sharing further supports this interpretation. All four tested great-grandchildren of William Webb Wagg share DNA with one or more descendants of his sisters, with substantial—but declining—representation among second, third, and fourth great-grandchildren. This gradient is entirely consistent with expectations for autosomal inheritance over successive generations.

The absence of identifiable shared matches from the Mary Ann Wegg and Adelaide Wegg lines is also fully accounted for. In both cases, documentary evidence confirms the existence of descendants, but testing availability, incomplete or inaccessible family trees, platform reporting thresholds, and expected DNA loss at this generational distance provide sufficient explanation for their non-representation. No shared-match patterns associated with these lines point toward an alternative parental family or contradict the evidence observed elsewhere.

Equally informative is what is not observed. Across all tested descendants of William Webb Wagg, no competing shared-match clusters consistently align with a different sibling group or an unrelated family. Where shared DNA is observed, it aligns specifically with the Sarah Ann Wegg and Susannah Wegg branches already established through documentary research.

Taken together, the documentary and autosomal DNA evidence converge on the same conclusion. The DNA does not introduce a new family structure or contradict the historical record; rather, it independently tests and supports it. The observed shared-match behaviour is exactly what would be expected if William Webb Wagg were one of the children of William and Mary Ann (Clark) Wegg of Norwich, separated from his siblings by transportation following his conviction rather than by parentage.

His later life in Australia reflects not a severing of family identity but its continuation: his English origins are acknowledged in his death notice, and the naming patterns within his Australian family mirror those of the Norwich Wegg household.

Methodological closing reflection

This analysis illustrates the strength of combining documentary research with autosomal DNA evidence when each is used within its proper limits. At fourth-cousin distance and beyond, autosomal DNA rarely provides certainty through any single match or centimorgan value. Its value lies instead in the convergence of patterns: repeatability across independent lines, consistency with documented chronology, and the absence of competing explanations.

In this case, the documentary record established a clear family framework before the DNA was examined. The DNA evidence was then used not to discover a family in the absence of records, but to test whether the reconstructed structure behaved as expected when viewed genetically. It does.

Having reached that point, the logical next step is to ask whether this combined approach can be extended further back in time. With William Webb Wagg securely placed within the Wegg family of Norwich, the next task is to assess whether documentary and DNA evidence can be used to push the line back another generation, testing the identities and relationships of William Wegg and Mary Ann Clark themselves.

That question lies beyond the scope of this post — but it is now a question that can be approached with confidence, using the same disciplined methodology applied here

Reader takeaway

This investigation asked a simple question: Does the DNA evidence behave as expected if William Webb Wagg belonged to the Wegg family of Norwich reconstructed from historical records?

The answer is yes.

Autosomal DNA shared between William Webb Wagg’s descendants and descendants of his sisters recurs across multiple independent lines, falls within expected relationship ranges, and diminishes predictably across generations. Where shared DNA is not observed, the absence is fully consistent with known family structures and the limits of autosomal inheritance at this distance.

Taken together, the documentary and DNA evidence converge on a single, coherent conclusion: William Webb Wagg was one of the children of William and Mary Ann (Clark) Wegg of Norwich, separated from his siblings by geographic distance, rather than by parentage.

This conclusion rests not on any single record or DNA match, but on the cumulative weight and internal consistency of the evidence as a whole.

William Webb Wagg investigation series

← Previous post: Roots in Norfolk

→ Next post: (To be published)

[1] See Finding the father of Beatrice Worrie (January 2026), https://webbwagg.blogspot.com/2026/01/finding-father-of-beatrice-worrie.html